There’s a peculiar way history arrives now.

It doesn’t usually kick in the door. It doesn’t shut off the power or empty the grocery shelves. It doesn’t announce itself with the physical authority of danger you can smell. It arrives through glass. Through a phone. Through a screen you can tilt, mute, or swipe away if it interferes with dinner.

That shift has consequences we haven’t fully reckoned with.

The great crises of the modern age often feel important without feeling immediate. Serious without feeling personal. Grave, yet strangely optional. We register them as information, not as threat. As events, not as ruptures.

This isn’t new. It’s just more efficient now.

January sixth landed this way for many people. Not as an interruption of daily life, but as a broadcast. Something that happened somewhere else, to someone else, while coffee still brewed and tomorrow’s alarm still waited.

That distance matters more than we like to admit.

We’re conditioned to think history announces itself loudly. With marching boots and smashed windows and unmistakable panic. But most turning points don’t arrive that way. They arrive quietly, wrapped in procedure, dressed in ambiguity, softened by normalcy.

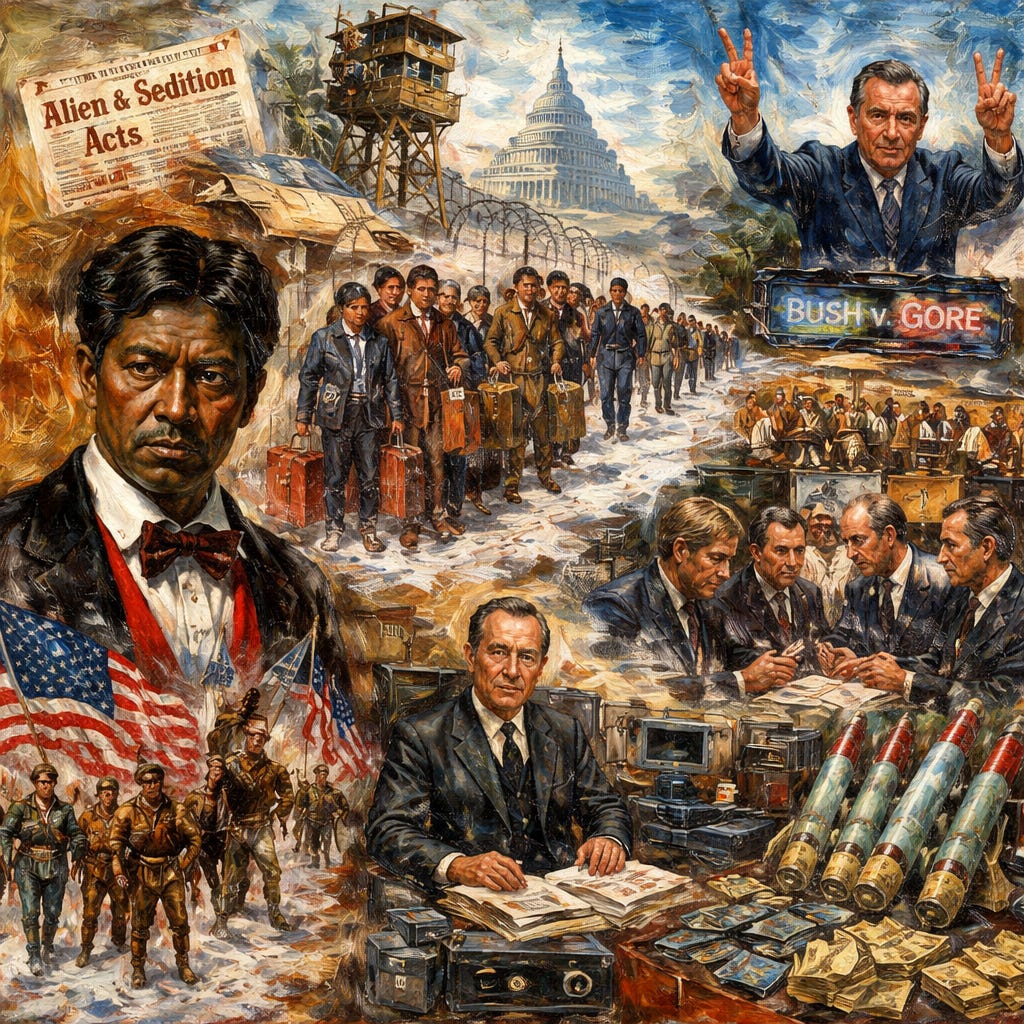

The Alien and Sedition Acts didn’t shut down daily life in 1798. Japanese American internment didn’t disrupt most households in 1942. A Supreme Court decision declaring that some people had no constitutional standing didn’t halt commerce in 1857. In each case, the routines held. The danger hid elsewhere.

The most dangerous damage is often done to things we can’t touch.

Democracy doesn’t live in buildings. It lives in shared agreement. In habits of restraint. In the collective decision to accept loss without burning the house down. Those things don’t bleed. They don’t shatter glass. They erode.

That makes them uniquely vulnerable in a mediated age.

When a challenge comes for a system rather than a street, it doesn’t always trip our instincts. There’s no adrenaline spike. No bodily signal that something is wrong. The nervous system stays calm because nothing has forced it to react.

If your lights stayed on, if your paycheck cleared, if your commute didn’t change, then the crisis remained abstract. Troubling, yes. Disturbing, yes. But not urgent in the way danger is urgent.

This is how existential threats slip past us.

An existential crisis isn’t defined by immediate collapse. It’s defined by altered possibility. By what becomes thinkable. By what’s tested, normalized, and quietly stored away for future use.

The danger isn’t what breaks in the moment. It’s what learns it can bend without consequence.

Watergate didn’t feel existential when it began. Iran Contra didn’t empty grocery stores. COINTELPRO didn’t announce itself at all. In each case, the real damage was not the act itself, but the lesson absorbed afterward about limits, enforcement, and accountability.

Think of a structure that develops a hairline fracture in a load bearing beam. The house doesn’t fall. The doors still open. The roof holds. From the inside, everything looks fine. But the margin for error has changed. Every added strain now carries more risk.

Living inside that house doesn’t feel dramatic. It feels familiar.

That’s why reasonable people can look at the same moment and come away with opposite conclusions. One group sees disruption and notes that the system survived. The other sees permission and understands that survival came at a cost.

They’re measuring different things.

One measures interruption. The other measures precedent.

History tends to side with the second group, but living through it rarely feels that way. Most institutional breakdowns don’t happen all at once. They happen through repeated tests that reveal where enforcement weakens, where norms become negotiable, where consequences depend on who you are.

From the inside, this feels boring. Administrative. Even tedious.

That’s the cruel paradox. The moments that matter most to the future often feel least dramatic in the present.

Modern life amplifies this effect. We exist in a constant churn of alerts, scandals, and manufactured urgency. Everything demands attention, which means nothing holds it for long. The nervous system adapts by flattening the peaks.

So when a genuine structural threat appears, it competes with everything else on the screen. A market dip. A celebrity meltdown. A viral distraction. They all arrive the same way, framed as content.

The mind treats them as equivalent because the medium insists they are.

This isn’t a moral failure. It’s a design problem.

We evolved to respond to danger we could see and feel. We didn’t evolve to sense the slow erosion of institutional trust delivered in high definition from a distance. We mistake continuity for safety because continuity is what our bodies recognize.

The trains still run. The checks still clear. The rituals continue. Therefore the system must be intact.

That logic has failed before.

It failed when internment camps were filled quietly. It failed when elections were decided by courts and absorbed without reckoning. It failed when surveillance expanded in secrecy and was only regretted later.

But systems don’t fail when routines stop. They fail when meaning drains out of those routines.

When elections happen without trust. When courts rule without legitimacy. When laws exist, but enforcement bends based on status. When the rules remain on paper while belief quietly slips away.

None of that changes your morning. It changes your future.

And because the consequences are delayed, responsibility disperses. Everyone waits for a moment that feels unmistakable. A moment that can’t be minimized or reframed or scrolled past.

By the time that moment arrives, if it does, the groundwork has already been laid.

This is the true impact of the remote.

It doesn’t make people indifferent. It makes danger feel theoretical until theory hardens into reality. It trains us to treat structural warnings as background noise. It encourages us to wait for emotion instead of evidence.

Democracy doesn’t survive on outrage. It survives on memory, accountability, and the refusal to confuse normalcy with health.

Screens can show us everything. They can’t make us feel responsible. That still requires intention.

And intention doesn’t autoplay.