The Revolutionary Conversion (2) - The Puritan Spine of America, a Seven Part Series

Opening

The American Revolution is usually told as an escape story.

An escape from kings, from inherited hierarchy, from the old world’s tightening grip. A people stepping out from divine right and into self rule. The beginning of something clean, rational, and new.

That story is reassuring. It’s also unfinished.

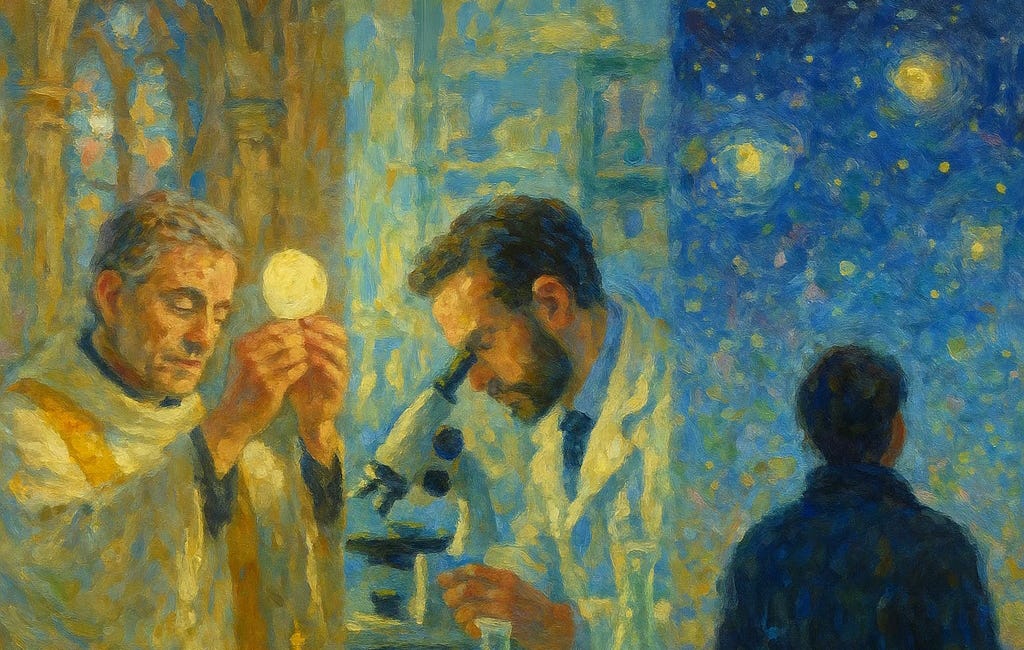

What the Revolution actually marks is not a rejection of moral inheritance, but its conversion. The old language was set aside. The emotional grammar stayed right where it was.

Read the founding documents closely and something familiar stirs beneath the Enlightenment polish. The cadence feels sermon shaped. The grievances are moral before they’re procedural. The argument doesn’t ask politely for reform. It pronounces judgment. This isn’t the voice of cautious negotiation. It’s the voice of a people convinced they’re right and increasingly convinced that history itself is on their side.

The colonies didn’t abandon the Puritan way of seeing the world. They translated it.

Providence became destiny. Election became exceptionalism. Covenant became national purpose. The city on a hill didn’t vanish. It was rebuilt with columns, footnotes, and appeals to natural rights.

That translation explains something we often glide past. How a rebellion against monarchy so quickly took on the tone of moral crusade. How liberty was framed not just as a political arrangement, but as a test of character. How corruption replaced sin as the great lurking danger, and vigilance replaced prayer as the civic obligation that never rests.

The Revolution secularized Puritan logic without draining its force. Theology receded. Judgment did not. Sermons gave way to declarations, but the habit of moral certainty remained firmly in place.

That’s why the Revolution often reads less like a legal brief and more like an exodus story retold by philosophers. Oppression is named. Pharaoh is identified. Deliverance is treated as inevitable. The people are chosen not by God this time, but by reason, by history, and by the self evident nature of their cause.

America didn’t leave its moral past behind in 1776. It folded it into the nation itself.

The king was gone.

The sermon remained.

The Secular Sermons of 1776

The Revolution announced itself as politics. It spoke like morality.

That’s the first thing we tend to miss if we read the founding texts too quickly, or too reverently. They don’t sound like arguments worked out in back rooms. They sound like judgments delivered with confidence.

There’s a familiar order to them. First comes the naming of injury. Not inconvenience. Injury. Then the careful stacking of offenses, one after another, patient and relentless. Then the diagnosis. Tyranny. Abuse. A pattern, not a fluke. And finally the conclusion, which arrives less as a proposal than as a moral fact. Separation isn’t simply allowed. It’s demanded.

This is sermon structure, translated.

The revolutionary pamphlets and declarations assume an audience already trained to hear this kind of speech. Trained to sit with long lists of grievance. Trained to feel the weight of accumulation. Trained to recognize the moment when endurance turns into obligation.

Nothing here asks, What should we do?

It asks, How long can we keep pretending we don’t already know?

That tone didn’t appear out of thin air. It came from a culture shaped by moral accounting, where history was read as a record of faithfulness and failure, where patterns mattered more than isolated acts, and where patience itself could slide into complicity.

So when the revolutionaries spoke of a long train of abuses, they weren’t reaching for a clever turn of phrase. They were speaking a language they already knew how to speak. The king wasn’t simply ineffective or misguided. He was unfit. His rule wasn’t just poor governance. It was corruption made visible.

That difference matters.

Political disagreements can be managed. Moral failures demand reckoning.

This is why the revolutionary voice rarely sounds tentative, even when the outcome was anything but certain. The language doesn’t hedge. It doesn’t wonder aloud. It declares. It indicts. It steadies itself through certainty.

And once certainty takes hold, it binds.

The new language of rights and representation carried forward the emotional force of older religious speech. The object changed. The posture did not. Where sermons once warned of spiritual decay, revolutionary texts warned of civic rot. Where ministers once spoke of judgment, patriots spoke of necessity.

Different nouns. Same cadence.

This also helps explain why compromise barely appears in the early revolutionary imagination. Compromise belongs to politics as process. Sermons move toward reckoning. They aim for confession, repentance, or separation. There’s little room for half measures once a problem has been named as moral failure.

By the time independence is declared, the decision feels less like a leap than a release.

The choice has already been made in the language itself.

1776 didn’t create moral urgency. It redirected it. The sermon stepped out of the meetinghouse and into the public square, carrying the same gravity, the same suspicion of corruption, and the same quiet confidence that history was watching.

The Revolution didn’t silence the Puritan voice.

It taught it to speak civics.

Natural Rights as Reframed Providence

The Revolution tells us it uncovered something obvious.

Natural rights are introduced as facts so plain they hardly need defense. Self evident. Already there. Beyond dispute. They don’t arise from bargaining or custom. They simply exist, waiting to be acknowledged.

That posture should sound familiar.

This is how providence once worked. It didn’t argue for itself. It made itself known through order, through outcome, through the quiet assurance that the world, rightly understood, already leaned in a certain direction. The Revolution didn’t discard that way of thinking. It changed the words.

Natural rights became the new given.

They carried moral certainty without explicit theology. Rights weren’t treated as delicate achievements of politics. They were treated as truths that stood before politics altogether. To deny them wasn’t merely to disagree. It was to violate something deeper than law.

That shift mattered.

If rights are natural, opposing them isn’t just an error. It’s corruption. If they’re self evident, resistance doesn’t call for persuasion so much as exposure. The argument moves away from competing interests and toward revealing blindness or bad faith.

This is providence recast in the language of reason.

Enlightenment philosophy gave the Revolution a universal voice, but it didn’t soften its moral intensity. Reason replaced revelation, but the structure stayed intact. There are truths that stand above human authority. There is a moral order that can be breached. There are consequences for those who place themselves against it.

The king’s central offense wasn’t simple misrule. It was defiance of what the revolutionaries understood as the natural order. He wasn’t wrong because the colonies objected. He was wrong because he stood on the wrong side of history itself.

That’s a powerful claim. It doesn’t invite deliberation. It asks for recognition.

Once rights are framed this way, politics begins to change its shape. Debate tightens. Doubt becomes suspect. Compromise starts to look like surrender to error. Moral clarity turns from aspiration into obligation.

Here the inherited emotional pattern shows itself most clearly. The Revolution left overt theology behind, but it held on to the comfort of inevitability. Things were going to unfold in a particular way because they were meant to.

Not by God this time.

By nature. By reason. By the assumed grain of the world.

Natural rights didn’t replace providence.

They took over its authority.

The Founders and the Puritan Tone They Couldn’t Escape

The founders liked to think of themselves as modern men.

They read widely. They argued fiercely. They distrusted clerics and bristled at inherited authority. Many of them took pains to signal distance from theology, superstition, and dogma. This was the age of reason, after all.

And yet, listen to the tone.

Read their letters, their speeches, the private cautions they passed among themselves, and a familiar moral register keeps surfacing. Power is spoken of as corrosive. Virtue is described as fragile. Decline is always nearby. The republic must be watched, guarded, restrained, or it will fail.

That’s not a neutral assessment. It’s a moral posture.

Even the most secular among them carried this cadence. John Adams worried incessantly about human nature and the need for virtue to hold the republic together. Thomas Jefferson wrote of liberty with almost devotional intensity, paired with deep suspicion of concentrated power. They spoke the language of reason, but the emotional rhythm was older than they cared to admit.

They didn’t escape the church.

They escaped its vocabulary.

What replaced it wasn’t moral restraint, but moral alertness. The threat was no longer damnation. It was corruption. The danger wasn’t sin. It was decay. But the sense of constant watchfulness remained, along with the fear that failure would be sweeping and irreversible.

This is where the Puritan inheritance shows itself most clearly. Not in doctrine, but in temperament.

The founders believed the republic could fail morally long before it failed structurally. That belief shaped everything from their warnings about factions to their insistence on restraint, balance, and limits on power. These weren’t just technical devices. They were moral defenses against a flawed human nature they no longer described in religious terms, but still deeply distrusted.

They assumed virtue would be demanded of citizens, not just institutions. Liberty was never treated as self sustaining. It required character. Discipline. Self control. The people would have to earn the republic again and again through conduct.

That’s a heavy expectation to place on a nation.

It carries an older conviction that a community’s fate rests on its moral seriousness. That decline doesn’t arrive all at once, but seeps in through neglect. That vigilance must be constant because erosion never sleeps.

The founders knew they were building something new.

They didn’t fully grasp how much of the old moral weather they carried with them as they built it.

They left the meetinghouse behind.

They kept its voice.

Virtue as the New Salvation

Once the old theology loosened its hold, something had to take its place.

The Revolution didn’t abandon the belief that moral effort mattered. It relocated it. Salvation shifted from the soul to the republic. What had once been a question of standing before God became a question of being worthy of freedom.

Virtue moved into the space belief once occupied.

This wasn’t treated as a lofty ideal or a personal preference. It was presented as a requirement. A republic, the founders insisted, could survive only if its citizens governed themselves before trying to govern anything else. Liberty without virtue wasn’t freedom. It was disorder waiting for an excuse.

That claim carries force because it isn’t gentle. It places moral responsibility squarely on the individual, not as a private matter, but as a public obligation. Character stops being personal. It becomes civic load bearing.

Earlier generations were warned that private failure endangered the whole community. Now citizens were warned that private self interest threatened the republic itself. The language shifted. The pressure stayed right where it was.

Virtue became proof of worthiness.

Here the inherited moral logic tightens. The Revolution didn’t offer freedom as a gift. It framed freedom as something that had to be continually deserved. The people weren’t simply liberated. They were placed under examination.

Fail that examination and the consequence wasn’t eternal punishment. It was national decline.

That fear runs straight through the early republican imagination. The warning repeats with steady confidence. A virtuous people can remain free. A corrupt people will lose everything. The logic is blunt. The stakes leave no room for ambiguity.

There’s comfort in this way of thinking. It explains success and failure cleanly. Prosperity becomes evidence of virtue. Trouble becomes a sign of moral lapse. The nation reads its fortunes the way earlier communities read signs in the sky or shifts in the season.

Once that habit sets in, it’s hard to shake.

Virtue as salvation also narrows sympathy. If freedom is earned through character, then those who fall short must have failed morally. Structural causes fade from view. Judgment steps forward. Responsibility hardens into verdict.

The Revolution didn’t release America from anxiety about purity and failure. It redirected it. The question was no longer whether one’s soul stood rightly before God.

It was whether the people were worthy of the republic they claimed to deserve.

The altar disappeared.

The demand didn’t.

Corruption Panic as Moral Reflex

If sin once carried the deepest fear, corruption soon took its place.

The Revolution didn’t create anxiety about moral failure. It redirected it toward power. Corruption became the word that absorbed everything the culture already worried about. Decay. Rot. Spread. The sense that once something slips, it rarely stays contained.

Corruption wasn’t treated as isolated misconduct. It was understood as a condition. Something that seeps in quietly. Something that grows through tolerance. Something that, once accepted, reshapes everything around it.

That framing matters.

When corruption is understood this way, it stops being a problem to manage and becomes a threat to remove. It isn’t something you correct and move past. It’s something you must confront before it settles in.

This reflex runs through early American political thinking. Power is dangerous not simply because it can lead to bad decisions, but because it can deform character. Office doesn’t just tempt wrongdoing. It changes the person who holds it. The fear isn’t error. It’s moral drift.

That’s an old anxiety speaking in secular terms.

Earlier generations worried that tolerated failure would bring judgment upon the whole community. Now the worry was that tolerated corruption would hollow out the republic from within. The object shifted. The fear remained.

This is where suspicion turns into virtue.

Watchfulness wasn’t optional. It was praised. Trust carried risk. Ease suggested neglect. Comfort hinted at complacency. A healthy republic was one that worried constantly about its own condition.

Calm began to look careless.

Confidence began to look naïve.

Anyone urging patience or restraint could be accused of blindness, or worse, quiet complicity.

Once corruption panic takes hold, politics acquires a permanent edge. Every disagreement carries moral weight. Every concession feels like surrender. Every failure becomes proof that something deeper has gone wrong.

It’s no accident that American political language so often tilts toward alarm. That habit formed early. The republic learned to see itself as always on the verge of internal decay, always vulnerable, always in need of scrutiny.

That posture can sharpen judgment.

It can also wear it down.

When corruption seems everywhere, nothing feels ordinary. Every action carries symbolic meaning. Every officeholder becomes suspect. The line between accountability and suspicion grows thin.

And yet, letting go of that reflex feels dangerous. To relax vigilance would feel irresponsible. To trust too freely would feel like moral failure.

So the panic stays.

The Revolution replaced fear of damnation with fear of decay.

It exchanged sin for corruption.

And it taught the republic to watch itself constantly, searching for signs that it might be losing what it believes keeps it worthy of survival.

The City on a Hill Becomes a Republic on a Pedestal

The city on a hill never really disappeared.

It relocated.

What began as a religious image of communal obligation was lifted, refined, and set at the level of the nation. The Revolution removed the theology from the phrase, but it kept the posture. America would still be watched. Still measured. Still judged. Only now the audience wasn’t God alone. It was the world.

Exceptionalism didn’t arrive sounding like pride. It arrived sounding like duty.

The republic wasn’t just free. It was exemplary. Its success would prove something. Its failure would warn others. America didn’t simply govern itself. It understood itself as being observed, compared, and weighed against its own claims.

That sense of elevation carried forward an older tension. To stand on a hill is to be visible. To stand on a pedestal is to be exposed. The Revolution didn’t promise anonymity among nations. It promised attention.

And attention brings pressure.

The country came to see itself not only through law or interest, but through meaning. Its existence carried purpose beyond survival. Its choices took on symbolic weight. Its internal struggles were never just internal. They reflected on the entire experiment.

This is how a republic becomes a moral example whether it intends to or not.

Success becomes confirmation. Failure becomes indictment. Ordinary political conflict turns into a judgment on national character. Prosperity suggests virtue. Crisis signals decline. The nation reads its condition the way earlier communities read favor and displeasure, carefully, anxiously, and with little patience for complexity.

Here again, the inherited emotional pattern asserts itself.

The pedestal demands coherence. It allows little space for contradiction or repair. To admit failure begins to sound like confession. To acknowledge complexity can feel like weakness. The higher the claim, the sharper the fall.

So the country learns to defend its image even as its reality strains. Critique starts to feel like betrayal. Dissent begins to sound like disloyalty. The line between moral concern and national pride grows thin.

The Revolution didn’t lift the burden of chosenness.

It expanded it.

America didn’t just free itself from a king. It placed itself before history as an example, carrying forward the older expectation that its fate would speak to something larger about the moral order of the world.

The hill remained.

The sermon widened.

The pedestal set.

Closing Pivot

The Revolution declared independence from a king.

That much is settled.

What remains unsettled is whether it ever declared independence from the moral inheritance it carried into the break. Theology faded. The structure stayed. Judgment survived the loss of doctrine. Purpose outlived providence.

America severed its tie to Britain, but it kept the habits that taught it to see itself as chosen, watched, and always on trial.

That inheritance gave the young republic seriousness and resolve. It also gave it rigidity. A tendency to treat politics as morality. A reflex that turns disagreement into indictment. A habit of confusing virtue with purity and vigilance with righteousness.

Once moral certainty becomes national, it doesn’t stay contained. It moves from church to state, from sermon to statute, from belief to punishment. The same logic that once sorted saints from sinners begins sorting citizens into worthy and unworthy, loyal and suspect.

The Revolution answered one question decisively.

Who rules?

It left another hanging in the air.

When did a nation founded on freedom learn how to live without a sermon running quietly in the background?

That unanswered question presses forward, into the next chapter, where inherited moral certainty hardens into judgment, and judgment begins to decide who is forgiven, who is punished, and who is permitted to belong.

A Question for the Reader

What happens to a republic when moral certainty outlives the faith that once restrained it?

Recommended Reading

Albion’s Seed

This is the deep origin story. Fischer shows how distinct British folkways carried moral habits, fears, and expectations into America long before independence. It will helps you see that what feels like ideology later often begins as temperament and mood.

The Metaphysical Club

Menand shows how American thinkers tried to live after certainty broke down. It’s a study of how moral seriousness survived the collapse of absolute belief and reappeared as pragmatism, reform, and civic responsibility. It pairs well with the argument about secularized moral logic.

Coming Next in The Puritan Spine

If the Revolution converted Puritan belief into civic purpose, the next question is what happened when that purpose began to harden.

The next essay turns from founding language to governing instinct. From virtue as aspiration to virtue as requirement. From moral seriousness to moral sorting.

It looks at how a culture trained to fear corruption slowly learned to favor punishment. How judgment became policy. How forgiveness slipped from public life. And how a nation once anxious about moral decline began building systems that make decline stick.

The sermon didn’t end with independence.

It entered the machinery.

Essay Three follows what happens when moral certainty stops calling people to vigilance and starts excusing punishment, and why America has always struggled to tell the difference.

Please Support the Work

Light Against Empire is free for all. If my words have value to you and you’re in a position to help, you can chip in with a monthly or yearly donation. Your support keeps the writing alive, the lights on, and the fire burning.

Further Reading: